Navier–Stokes equations

| Continuum mechanics | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

The Navier–Stokes equations, named after Claude-Louis Navier and George Gabriel Stokes, describe the motion of fluid substances. These equations arise from applying Newton's second law to fluid motion, together with the assumption that the fluid stress is the sum of a diffusing viscous term (proportional to the gradient of velocity), plus a pressure term.

The equations are useful because they describe the physics of many things of academic and economic interest. They may be used to model the weather, ocean currents, water flow in a pipe, air flow around a wing, and motion of stars inside a galaxy. The Navier–Stokes equations in their full and simplified forms help with the design of aircraft and cars, the study of blood flow, the design of power stations, the analysis of pollution, and many other things. Coupled with Maxwell's equations they can be used to model and study magnetohydrodynamics.

The Navier–Stokes equations are also of great interest in a purely mathematical sense. Somewhat surprisingly, given their wide range of practical uses, mathematicians have not yet proven that in three dimensions solutions always exist (existence), or that if they do exist, then they do not contain any singularity (smoothness). These are called the Navier–Stokes existence and smoothness problems. The Clay Mathematics Institute has called this one of the seven most important open problems in mathematics and has offered a US$1,000,000 prize for a solution or a counter-example.[1]

The Navier–Stokes equations dictate not position but rather velocity. A solution of the Navier–Stokes equations is called a velocity field or flow field, which is a description of the velocity of the fluid at a given point in space and time. Once the velocity field is solved for, other quantities of interest (such as flow rate or drag force) may be found. This is different from what one normally sees in classical mechanics, where solutions are typically trajectories of position of a particle or deflection of a continuum. Studying velocity instead of position makes more sense for a fluid; however for visualization purposes one can compute various trajectories.

Contents |

Properties

Nonlinearity

The Navier–Stokes equations are nonlinear partial differential equations in almost every real situation. In some cases, such as one-dimensional flow and Stokes flow (or creeping flow), the equations can be simplified to linear equations. The nonlinearity makes most problems difficult or impossible to solve and is the main contributor to the turbulence that the equations model.

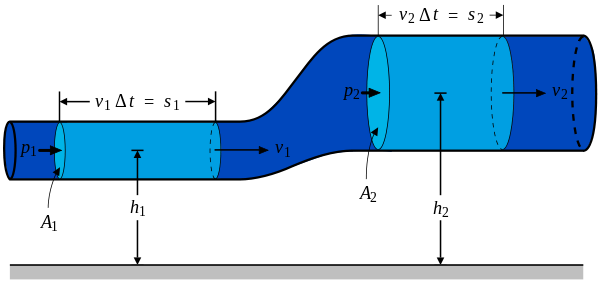

The nonlinearity is due to convective acceleration, which is an acceleration associated with the change in velocity over position. Hence, any convective flow, whether turbulent or not, will involve nonlinearity, an example of convective but laminar (nonturbulent) flow would be the passage of a viscous fluid (for example, oil) through a small converging nozzle. Such flows, whether exactly solvable or not, can often be thoroughly studied and understood.

Turbulence

Turbulence is the time dependent chaotic behavior seen in many fluid flows. It is generally believed that it is due to the inertia of the fluid as a whole: the culmination of time dependent and convective acceleration; hence flows where inertial effects are small tend to be laminar (the Reynolds number quantifies how much the flow is affected by inertia). It is believed, though not known with certainty, that the Navier–Stokes equations describe turbulence properly.

The numerical solution of the Navier–Stokes equations for turbulent flow is extremely difficult, and due to the significantly different mixing-length scales that are involved in turbulent flow, the stable solution of this requires such a fine mesh resolution that the computational time becomes significantly infeasible for calculation (see Direct numerical simulation). Attempts to solve turbulent flow using a laminar solver typically result in a time-unsteady solution, which fails to converge appropriately. To counter this, time-averaged equations such as the Reynolds-averaged Navier-Stokes equations (RANS), supplemented with turbulence models (such as the k-ε model), are used in practical computational fluid dynamics (CFD) applications when modeling turbulent flows. Another technique for solving numerically the Navier–Stokes equation is the Large eddy simulation (LES). This approach is computationally more expensive than the RANS method (in time and computer memory), but produces better results since the larger turbulent scales are explicitly resolved.

Applicability

Together with supplemental equations (for example, conservation of mass) and well formulated boundary conditions, the Navier–Stokes equations seem to model fluid motion accurately; even turbulent flows seem (on average) to agree with real world observations.

The Navier–Stokes equations assume that the fluid being studied is a Continuum not moving at relativistic velocities. At very small scales or under extreme conditions, real fluids made out of discrete molecules will produce results different from the continuous fluids modeled by the Navier–Stokes equations. Depending on the Knudsen number of the problem, statistical mechanics or possibly even molecular dynamics may be a more appropriate approach.

Another limitation is very simply the complicated nature of the equations. Time tested formulations exist for common fluid families, but the application of the Navier–Stokes equations to less common families tends to result in very complicated formulations which are an area of current research. For this reason, these equations are usually written for Newtonian fluids. Studying such fluids is "simple" because the viscosity model ends up being linear; truly general models for the flow of other kinds of fluids (such as blood) do not, as of 2010, exist.

Derivation and description

The derivation of the Navier–Stokes equations begins with an application of Newton's second law: conservation of momentum (often alongside mass and energy conservation) being written for an arbitrary portion of the fluid. In an inertial frame of reference, the general form of the equations of fluid motion is:[2]

where  is the flow velocity,

is the flow velocity,  is the fluid density, p is the pressure,

is the fluid density, p is the pressure,  is the (deviatoric) stress tensor, and

is the (deviatoric) stress tensor, and  represents body forces (per unit volume) acting on the fluid and

represents body forces (per unit volume) acting on the fluid and  is the del operator. This is a statement of the conservation of momentum in a fluid and it is an application of Newton's second law to a Continuum; in fact this equation is applicable to any non-relativistic continuum and is known as the Cauchy momentum equation.

is the del operator. This is a statement of the conservation of momentum in a fluid and it is an application of Newton's second law to a Continuum; in fact this equation is applicable to any non-relativistic continuum and is known as the Cauchy momentum equation.

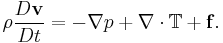

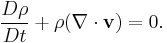

This equation is often written using the substantive derivative Dv/Dt, making it more apparent that this is a statement of Newton's second law:

The left side of the equation describes acceleration, and may be composed of time dependent or convective effects (also the effects of non-inertial coordinates if present). The right side of the equation is in effect a summation of body forces (such as gravity) and divergence of stress (pressure and shear stress).

Convective acceleration

A very significant feature of the Navier–Stokes equations is the presence of convective acceleration: the effect of time independent acceleration of a fluid with respect to space. While individual fluid particles are indeed experiencing time dependent acceleration, the convective acceleration of the flow field is a spatial effect, one example being fluid speeding up in a nozzle. Convective acceleration is represented by the nonlinear quantity:

which may be interpreted either as  or as

or as  with

with  the tensor derivative of the velocity vector

the tensor derivative of the velocity vector  Both interpretations give the same result, independent of the coordinate system — provided

Both interpretations give the same result, independent of the coordinate system — provided  is interpreted as the covariant derivative.[3]

is interpreted as the covariant derivative.[3]

Interpretation as (v·∇)v

The convection term is often written as

where the advection operator  is used. Usually this representation is preferred because it is simpler than the one in terms of the tensor derivative

is used. Usually this representation is preferred because it is simpler than the one in terms of the tensor derivative  [3]

[3]

Interpretation as v·(∇v)

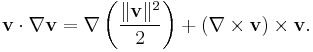

Here  is the tensor derivative of the velocity vector, equal in Cartesian coordinates to the component by component gradient. The convection term may, by a vector calculus identity, be expressed without a tensor derivative:[4][5]

is the tensor derivative of the velocity vector, equal in Cartesian coordinates to the component by component gradient. The convection term may, by a vector calculus identity, be expressed without a tensor derivative:[4][5]

The form has use in irrotational flow, where the curl of the velocity (called vorticity)  is equal to zero.

is equal to zero.

Regardless of what kind of fluid is being dealt with, convective acceleration is a nonlinear effect. Convective acceleration is present in most flows (exceptions include one-dimensional incompressible flow), but its dynamic effect is disregarded in creeping flow (also called Stokes flow) .

Stresses

The effect of stress in the fluid is represented by the  and

and  terms, these are gradients of surface forces, analogous to stresses in a solid.

terms, these are gradients of surface forces, analogous to stresses in a solid.  is called the pressure gradient and arises from the isotropic part of the stress tensor. This part is given by normal stresses that turn up in almost all situations, dynamic or not. The anisotropic part of the stress tensor gives rise to

is called the pressure gradient and arises from the isotropic part of the stress tensor. This part is given by normal stresses that turn up in almost all situations, dynamic or not. The anisotropic part of the stress tensor gives rise to  , which conventionally describes viscous forces; for incompressible flow, this is only a shear effect. Thus,

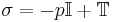

, which conventionally describes viscous forces; for incompressible flow, this is only a shear effect. Thus,  is the deviatoric stress tensor, and the stress tensor is equal to:[6]

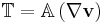

is the deviatoric stress tensor, and the stress tensor is equal to:[6]

where  is the 3×3 identity matrix. Interestingly, only the gradient of pressure matters, not the pressure itself. The effect of the pressure gradient is that fluid flows from high pressure to low pressure.

is the 3×3 identity matrix. Interestingly, only the gradient of pressure matters, not the pressure itself. The effect of the pressure gradient is that fluid flows from high pressure to low pressure.

The stress terms p and  are yet unknown, so the general form of the equations of motion is not usable to solve problems. Besides the equations of motion—Newton's second law—a force model is needed relating the stresses to the fluid motion.[7] For this reason, assumptions on the specific behavior of a fluid are made (based on natural observations) and applied in order to specify the stresses in terms of the other flow variables, such as velocity and density.

are yet unknown, so the general form of the equations of motion is not usable to solve problems. Besides the equations of motion—Newton's second law—a force model is needed relating the stresses to the fluid motion.[7] For this reason, assumptions on the specific behavior of a fluid are made (based on natural observations) and applied in order to specify the stresses in terms of the other flow variables, such as velocity and density.

The Navier–Stokes equations result from the following assumptions on the deviatoric stress tensor  :[8]

:[8]

- the deviatoric stress vanishes for a fluid at rest, and – by Galilean invariance – also does not depend directly on the flow velocity itself, but only on spatial derivatives of the flow velocity

- in the Navier–Stokes equations, the deviatoric stress is expressed as the product of the tensor gradient

of the flow velocity with a viscosity tensor

of the flow velocity with a viscosity tensor  , i.e. :

, i.e. :

- the fluid is assumed to be isotropic, as valid for gases and simple liquids, and consequently

is an isotropic tensor; furthermore, since the deviatoric stress tensor is symmetric, it turns out that it can be expressed in terms of two scalar dynamic viscosities μ and μ”:

is an isotropic tensor; furthermore, since the deviatoric stress tensor is symmetric, it turns out that it can be expressed in terms of two scalar dynamic viscosities μ and μ”:  where

where  is the rate-of-strain tensor and

is the rate-of-strain tensor and  is the rate of expansion of the flow

is the rate of expansion of the flow - the deviatoric stress tensor has zero trace, so for a three-dimensional flow 2μ + 3μ” = 0

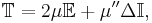

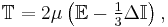

As a result, in the Navier–Stokes equations the deviatoric stress tensor has the following form:[8]

with the quantity between brackets the non-isotropic part of the rate-of-strain tensor  The dynamic viscosity μ does not need to be constant – in general it depends on conditions like temperature and pressure, and in turbulence modelling the concept of eddy viscosity is used to approximate the average deviatoric stress.

The dynamic viscosity μ does not need to be constant – in general it depends on conditions like temperature and pressure, and in turbulence modelling the concept of eddy viscosity is used to approximate the average deviatoric stress.

The pressure p is modelled by use of an equation of state.[9] For the special case of an incompressible flow, the pressure constrains the flow in such a way that the volume of fluid elements is constant: isochoric flow resulting in a solenoidal velocity field with  [10]

[10]

Other forces

The vector field  represents "other" (body force) forces. Typically this is only gravity, but may include other fields (such as electromagnetic). In a non-inertial coordinate system, other "forces" such as that associated with rotating coordinates may be inserted.

represents "other" (body force) forces. Typically this is only gravity, but may include other fields (such as electromagnetic). In a non-inertial coordinate system, other "forces" such as that associated with rotating coordinates may be inserted.

Often, these forces may be represented as the gradient of some scalar quantity. Gravity in the z direction, for example, is the gradient of  . Since pressure shows up only as a gradient, this implies that solving a problem without any such body force can be mended to include the body force by modifying pressure.

. Since pressure shows up only as a gradient, this implies that solving a problem without any such body force can be mended to include the body force by modifying pressure.

Other equations

The Navier–Stokes equations are strictly a statement of the conservation of momentum. In order to fully describe fluid flow, more information is needed (how much depends on the assumptions made), this may include boundary data (no-slip, capillary surface, etc.), the conservation of mass, the conservation of energy, and/or an equation of state.

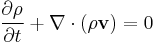

Regardless of the flow assumptions, a statement of the conservation of mass is generally necessary. This is achieved through the mass continuity equation, given in its most general form as:

or, using the substantive derivative:

Incompressible flow of Newtonian fluids

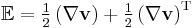

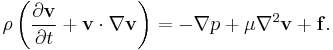

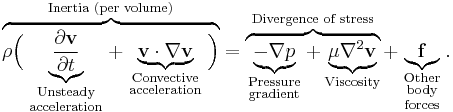

A simplification of the resulting flow equations is obtained when considering an incompressible flow of a Newtonian fluid. The assumption of incompressibility rules out the possibility of sound or shock waves to occur; so this simplification is invalid if these phenomena are important. The incompressible flow assumption typically holds well even when dealing with a "compressible" fluid — such as air at room temperature — at low Mach numbers (even when flowing up to about Mach 0.3). Taking the incompressible flow assumption into account and assuming constant viscosity, the Navier–Stokes equations will read, in vector form:[11]

Here f represents "other" body forces (forces per unit volume), such as gravity or centrifugal force. The shear stress term  becomes the useful quantity

becomes the useful quantity  when the fluid is assumed incompressible and Newtonian, where

when the fluid is assumed incompressible and Newtonian, where  is the dynamic viscosity.[12]

is the dynamic viscosity.[12]

It's well worth observing the meaning of each term (compare to the Cauchy momentum equation):

Note that only the convective terms are nonlinear for incompressible Newtonian flow. The convective acceleration is an acceleration caused by a (possibly steady) change in velocity over position, for example the speeding up of fluid entering a converging nozzle. Though individual fluid particles are being accelerated and thus are under unsteady motion, the flow field (a velocity distribution) will not necessarily be time dependent.

Another important observation is that the viscosity is represented by the vector Laplacian of the velocity field (interpreted here as the difference between the velocity at a point and the mean velocity in a small volume around). This implies that Newtonian viscosity is diffusion of momentum, this works in much the same way as the diffusion of heat seen in the heat equation (which also involves the Laplacian).

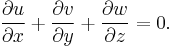

If temperature effects are also neglected, the only "other" equation (apart from initial/boundary conditions) needed is the mass continuity equation. Under the incompressible assumption, density is a constant and it follows that the equation will simplify to:

This is more specifically a statement of the conservation of volume (see divergence).

These equations are commonly used in 3 coordinates systems: Cartesian, cylindrical, and spherical. While the Cartesian equations seem to follow directly from the vector equation above, the vector form of the Navier–Stokes equation involves some tensor calculus which means that writing it in other coordinate systems is not as simple as doing so for scalar equations (such as the heat equation).

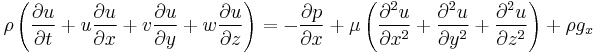

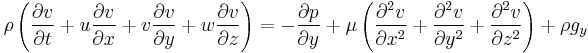

Cartesian coordinates

Writing the vector equation explicitly,

Note that gravity has been accounted for as a body force, and the values of  will depend on the orientation of gravity with respect to the chosen set of coordinates.

will depend on the orientation of gravity with respect to the chosen set of coordinates.

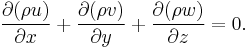

The continuity equation reads:

When the flow is at steady-state,  does not change with respect to time. The continuity equation is reduced to:

does not change with respect to time. The continuity equation is reduced to:

When the flow is incompressible,  is constant and does not change with respect to space. The continuity equation is reduced to:

is constant and does not change with respect to space. The continuity equation is reduced to:

The velocity components (the dependent variables to be solved for) are typically named u, v, w. This system of four equations comprises the most commonly used and studied form. Though comparatively more compact than other representations, this is still a nonlinear system of partial differential equations for which solutions are difficult to obtain.

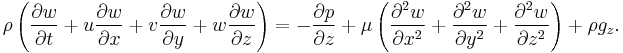

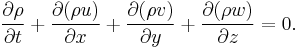

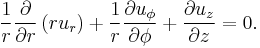

Cylindrical coordinates

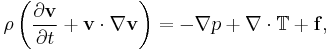

A change of variables on the Cartesian equations will yield[11] the following momentum equations for r,  , and z:

, and z:

The gravity components will generally not be constants, however for most applications either the coordinates are chosen so that the gravity components are constant or else it is assumed that gravity is counteracted by a pressure field (for example, flow in horizontal pipe is treated normally without gravity and without a vertical pressure gradient). The continuity equation is:

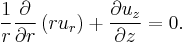

This cylindrical representation of the incompressible Navier–Stokes equations is the second most commonly seen (the first being Cartesian above). Cylindrical coordinates are chosen to take advantage of symmetry, so that a velocity component can disappear. A very common case is axisymmetric flow with the assumption of no tangential velocity ( ), and the remaining quantities are independent of

), and the remaining quantities are independent of  :

:

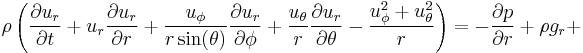

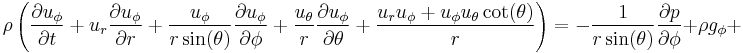

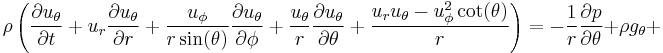

Spherical coordinates

In spherical coordinates, the r,  , and

, and  momentum equations are[11] (note the convention used:

momentum equations are[11] (note the convention used:  is colatitude[13]):

is colatitude[13]):

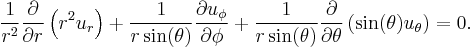

Mass continuity will read:

These equations could be (slightly) compacted by, for example, factoring  from the viscous terms. However, doing so would undesirably alter the structure of the Laplacian and other quantities.

from the viscous terms. However, doing so would undesirably alter the structure of the Laplacian and other quantities.

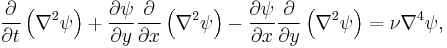

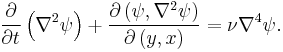

Stream function formulation

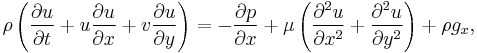

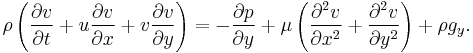

Taking the curl of the Navier–Stokes equation results in the elimination of pressure. This is especially easy to see if 2D Cartesian flow is assumed ( and no dependence of anything on z), where the equations reduce to:

and no dependence of anything on z), where the equations reduce to:

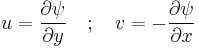

Differentiating the first with respect to y, the second with respect to x and subtracting the resulting equations will eliminate pressure and any potential force. Defining the stream function  through

through

results in mass continuity being unconditionally satisfied (given the stream function is continuous), and then incompressible Newtonian 2D momentum and mass conservation degrade into one equation:

where  is the (2D) biharmonic operator and

is the (2D) biharmonic operator and  is the kinematic viscosity,

is the kinematic viscosity,  . We can also express this compactly using the Jacobian determinant:

. We can also express this compactly using the Jacobian determinant:

This single equation together with appropriate boundary conditions describes 2D fluid flow, taking only kinematic viscosity as a parameter. Note that the equation for creeping flow results when the left side is assumed zero.

In axisymmetric flow another stream function formulation, called the Stokes stream function, can be used to describe the velocity components of an incompressible flow with one scalar function.

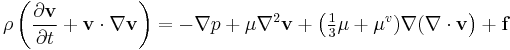

Compressible flow of Newtonian fluids

There are some phenomena that are closely linked with fluid compressibility. One of the obvious examples is sound. Description of such phenomena requires more general presentation of the Navier–Stokes equation that takes into account fluid compressibility. If viscosity is assumed a constant, one additional term appears, as shown here:[14][15]

where  is the volume viscosity coefficient, also known as second viscosity coefficient or bulk viscosity. This additional term disappears for an incompressible fluid, when the divergence of the flow equals zero.

is the volume viscosity coefficient, also known as second viscosity coefficient or bulk viscosity. This additional term disappears for an incompressible fluid, when the divergence of the flow equals zero.

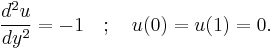

Application to specific problems

The Navier–Stokes equations, even when written explicitly for specific fluids, are rather generic in nature and their proper application to specific problems can be very diverse. This is partly because there is an enormous variety of problems that may be modeled, ranging from as simple as the distribution of static pressure to as complicated as multiphase flow driven by surface tension.

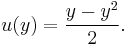

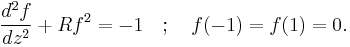

Generally, application to specific problems begins with some flow assumptions and initial/boundary condition formulation, this may be followed by scale analysis to further simplify the problem. For example, after assuming steady, parallel, one dimensional, nonconvective pressure driven flow between parallel plates, the resulting scaled (dimensionless) boundary value problem is:

The boundary condition is the no slip condition. This problem is easily solved for the flow field:

From this point onward more quantities of interest can be easily obtained, such as viscous drag force or net flow rate.

Difficulties may arise when the problem becomes slightly more complicated. A seemingly modest twist on the parallel flow above would be the radial flow between parallel plates; this involves convection and thus nonlinearity. The velocity field may be represented by a function  that must satisfy:

that must satisfy:

This ordinary differential equation is what is obtained when the Navier–Stokes equations are written and the flow assumptions applied (additionally, the pressure gradient is solved for). The nonlinear term makes this a very difficult problem to solve analytically (a lengthy implicit solution may be found which involves elliptic integrals and roots of cubic polynomials). Issues with the actual existence of solutions arise for R > 1.41 (approximately. This is not the square root of two), the parameter R being the Reynolds number with appropriately chosen scales. This is an example of flow assumptions losing their applicability, and an example of the difficulty in "high" Reynolds number flows.

Some exact solutions to the Navier–Stokes equations exist. Examples of degenerate cases — with the non-linear terms in the Navier–Stokes equations equal to zero — are Poiseuille flow, Couette flow and the oscillatory Stokes boundary layer. But also more interesting examples, solutions to the full non-linear equations, exist; for example the Taylor–Green vortex.[16][17][18] Note that the existence of these exact solutions does not imply they are stable: turbulence may develop at higher Reynolds numbers.

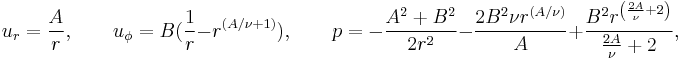

For example, in the case of an unbounded planar domain with two-dimensional — incompressible and stationary — flow in polar coordinates  the velocity components

the velocity components  and pressure p are:[19]

and pressure p are:[19]

where A and B are arbitrary constants. This solution is valid in the domain r ≥ 1 and for

Wyld diagrams

Wyld diagrams are bookkeeping graphs that correspond to the Navier–Stokes equations via a perturbation expansion of the fundamental continuum mechanics. Similar to the Feynman diagrams in quantum field theory, these diagrams are an extension of Keldysh's technique for nonequilibrium processes in fluid dynamics. In other words, these diagrams assign graphs to the (often) turbulent phenomena in turbulent fluids by allowing correlated and interacting fluid particles to obey stochastic processes associated to pseudo-random functions in probability distributions.[20]

See also

- Boltzmann equation

- Churchill–Bernstein equation

- Coandă effect

- Computational fluid dynamics

- Fokker–Planck equation

- Large eddy simulation

- Mach number

- Navier–Stokes existence and smoothness — one of the Millennium Prize Problems as stated by the Clay Mathematics Institute

- Multiphase flow

- Reynolds transport theorem

- Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes equations

- Adhémar Jean Claude Barré de Saint-Venant

- Vlasov equation

Notes

- ↑ Millennium Prize Problems, Clay Mathematics Institute, http://www.claymath.org/millennium/, retrieved 2009-04-11

- ↑ Batchelor (1967) pp. 137 & 142.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Emanuel, G. (2001), Analytical fluid dynamics (second ed.), CRC Press, ISBN 0849391148 pp. 6–7.

- ↑ See Batchelor (1967), §3.5, p. 160.

- ↑ Eric W. Weisstein, Convective Derivative, MathWorld, http://mathworld.wolfram.com/ConvectiveDerivative.html, retrieved 2008-05-20

- ↑ Batchelor (1967) p. 142.

- ↑ Feynman, Richard P.; Leighton, Robert B.; Sands, Matthew (1963), The Feynman Lectures on Physics, Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley, ISBN 0-201-02116-1, Vol. 1, §9–4 and §12–1.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Batchelor (1967) pp. 142–148.

- ↑ Batchelor (1967) p. 165.

- ↑ Batchelor (1967) p. 75.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 See Acheson (1990).

- ↑ Batchelor (1967) pp. 21 & 147.

- ↑ Eric W. Weisstein (2005-10-26), Spherical Coordinates, MathWorld, http://mathworld.wolfram.com/SphericalCoordinates.html, retrieved 2008-01-22

- ↑ Landau & Lifshitz (1987) pp. 44–45.

- ↑ Batchelor (1967) pp. 147 & 154.

- ↑ Wang, C.Y. (1991), "Exact solutions of the steady-state Navier–Stokes equations", Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics 23: 159–177, doi:10.1146/annurev.fl.23.010191.001111

- ↑ Landau & Lifshitz (1987) pp. 75–88.

- ↑ Ethier, C.R.; Steinman, D.A. (1994), "Exact fully 3D Navier–Stokes solutions for benchmarking", International Journal for Numerical Methods in Fluids 19 (5): 369–375, doi:10.1002/fld.1650190502

- ↑ Ladyzhenskaya, O.A. (1969), The Mathematical Theory of viscous Incompressible Flow (2nd ed.), p. preface, xi

- ↑ McComb, W.D. (2008), Renormalization methods: A guide for beginners, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0199236526 pp. 121–128.

References

- Acheson, D. J. (1990), Elementary Fluid Dynamics, Oxford Applied Mathematics and Computing Science Series, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0198596790

- Batchelor, G.K. (1967), An Introduction to Fluid Dynamics, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521663962

- Landau, L. D.; Lifshitz, E. M. (1987), Fluid mechanics, Course of Theoretical Physics, 6 (2nd revised ed.), Pergamon Press, ISBN 0 08 033932 8, OCLC 15017127

- Rhyming, Inge L. (1991), Dynamique des fluides, Presses Polytechniques et Universitaires Romandes, Lausanne

- Polyanin, A.D.; Kutepov, A.M.; Vyazmin, A.V.; Kazenin, D.A. (2002), Hydrodynamics, Mass and Heat Transfer in Chemical Engineering, Taylor & Francis, London, ISBN 0-415-27237-8

- Currie, I. G. (1974), Fundamental Mechanics of Fluids, McGraw-Hill, ISBN 0070150001

External links

- Simplified derivation of the Navier–Stokes equations

- http://www.claymath.org/millennium/Navier-Stokes_Equations/navierstokes.pdf Millennium Prize problem description.

- CFD online software list A compilation of codes, including Navier–Stokes solvers.

![r:\;\;\rho \left(\frac{\partial u_r}{\partial t} + u_r \frac{\partial u_r}{\partial r} + \frac{u_{\phi}}{r} \frac{\partial u_r}{\partial \phi} + u_z \frac{\partial u_r}{\partial z} - \frac{u_{\phi}^2}{r}\right) =

-\frac{\partial p}{\partial r} +

\mu \left[\frac{1}{r}\frac{\partial}{\partial r}\left(r \frac{\partial u_r}{\partial r}\right) + \frac{1}{r^2}\frac{\partial^2 u_r}{\partial \phi^2} + \frac{\partial^2 u_r}{\partial z^2}-\frac{u_r}{r^2}-\frac{2}{r^2}\frac{\partial u_\phi}{\partial \phi} \right] + \rho g_r](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/1167391da9a316b25ffd67f3bffc0bef.png)

![\phi:\;\;\rho \left(\frac{\partial u_{\phi}}{\partial t} + u_r \frac{\partial u_{\phi}}{\partial r} + \frac{u_{\phi}}{r} \frac{\partial u_{\phi}}{\partial \phi} + u_z \frac{\partial u_{\phi}}{\partial z} + \frac{u_r u_{\phi}}{r}\right) =

-\frac{1}{r}\frac{\partial p}{\partial \phi} +

\mu \left[\frac{1}{r}\frac{\partial}{\partial r}\left(r \frac{\partial u_{\phi}}{\partial r}\right) + \frac{1}{r^2}\frac{\partial^2 u_{\phi}}{\partial \phi^2} + \frac{\partial^2 u_{\phi}}{\partial z^2} + \frac{2}{r^2}\frac{\partial u_r}{\partial \phi} - \frac{u_{\phi}}{r^2}\right] + \rho g_{\phi}](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/628dc5cefddd1f399045924981fa3b4b.png)

![z:\;\;\rho \left(\frac{\partial u_z}{\partial t} + u_r \frac{\partial u_z}{\partial r} + \frac{u_{\phi}}{r} \frac{\partial u_z}{\partial \phi} + u_z \frac{\partial u_z}{\partial z}\right) =

-\frac{\partial p}{\partial z} + \mu \left[\frac{1}{r}\frac{\partial}{\partial r}\left(r \frac{\partial u_z}{\partial r}\right) + \frac{1}{r^2}\frac{\partial^2 u_z}{\partial \phi^2} + \frac{\partial^2 u_z}{\partial z^2}\right] + \rho g_z.](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/d14890e804f624381608dee326a47eea.png)

![\rho \left(\frac{\partial u_r}{\partial t} + u_r \frac{\partial u_r}{\partial r} + u_z \frac{\partial u_r}{\partial z}\right) =

-\frac{\partial p}{\partial r} +

\mu \left[\frac{1}{r}\frac{\partial}{\partial r}\left(r \frac{\partial u_r}{\partial r}\right) + \frac{\partial^2 u_r}{\partial z^2} - \frac{u_r}{r^2}\right] + \rho g_r](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/2952426230bd03380beecc2af09a34ee.png)

![\rho \left(\frac{\partial u_z}{\partial t} + u_r \frac{\partial u_z}{\partial r} + u_z \frac{\partial u_z}{\partial z}\right) =

-\frac{\partial p}{\partial z} + \mu \left[\frac{1}{r}\frac{\partial}{\partial r}\left(r \frac{\partial u_z}{\partial r}\right) + \frac{\partial^2 u_z}{\partial z^2}\right] + \rho g_z](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/a8b5e1e44ca083f6aa146d971bb60684.png)

![\mu \left[

\frac{1}{r^2} \frac{\partial}{\partial r}\left(r^2 \frac{\partial u_r}{\partial r}\right) +

\frac{1}{r^2 \sin(\theta)^2} \frac{\partial^2 u_r}{\partial \phi^2} +

\frac{1}{r^2 \sin(\theta)} \frac{\partial}{\partial \theta}\left(\sin(\theta) \frac{\partial u_r}{\partial \theta}\right) -

2 \frac{u_r + \frac{\partial u_{\theta}}{\partial \theta} + u_{\theta} \cot(\theta)}{r^2} +

\frac{2}{r^2 \sin(\theta)} \frac{\partial u_{\phi}}{\partial \phi}

\right]](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/277f62763209368baf8d6cbc65449e4f.png)

![\mu \left[

\frac{1}{r^2} \frac{\partial}{\partial r}\left(r^2 \frac{\partial u_{\phi}}{\partial r}\right) +

\frac{1}{r^2 \sin(\theta)^2} \frac{\partial^2 u_{\phi}}{\partial \phi^2} +

\frac{1}{r^2 \sin(\theta)} \frac{\partial}{\partial \theta}\left(\sin(\theta) \frac{\partial u_{\phi}}{\partial \theta}\right) +

\frac{2 \frac{\partial u_r}{\partial \phi} + 2 \cos(\theta) \frac{\partial u_{\theta}}{\partial \phi} - u_{\phi}}{r^2 \sin(\theta)^2}

\right]](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/3b7a5750aa2a4080015f4e71c0f9e8b1.png)

![\mu \left[

\frac{1}{r^2} \frac{\partial}{\partial r}\left(r^2 \frac{\partial u_{\theta}}{\partial r}\right) +

\frac{1}{r^2 \sin(\theta)^2} \frac{\partial^2 u_{\theta}}{\partial \phi^2} +

\frac{1}{r^2 \sin(\theta)} \frac{\partial}{\partial \theta}\left(\sin(\theta) \frac{\partial u_{\theta}}{\partial \theta}\right) +

\frac{2}{r^2} \frac{\partial u_r}{\partial \theta} -

\frac{u_{\theta} + 2 \cos(\theta) \frac{\partial u_{\phi}}{\partial \phi}}{r^2 \sin(\theta)^2}

\right].](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/f65ab138f15e63b5326d67550ea14a04.png)